Propolis Bee Resin — How to Harvest and Process It

PROPOLIS, PROPOLIS TRAPS & OTHER EQUIPMENT AVAILABLE FROM OUR STORE >>

Hives, swarm traps, honey extractors, etc.

In addition to nectar, pollen, and water, bees collect plant resins to make fragrant and healthful propolis, which they use for sanitizing the nest (it kills germs), sealing cracks, and reinforcing waxen honeycombs. Propolis is a very valuable hive product, and easy to harvest without disturbing the bees — just scrape it off your frames and hive walls. Better still, use a special screen called propolis collector or propolis trap.

How to use a propolis collector

Bees have an instinct to seal cracks in their nest with propolis, to exclude drafts, pests, and bacteria. A propolis collector is a grooved/perforated screen made from flexible food-grade plastic. The perforations are too small for the bees to pass through; under the right conditions bees will fill these with propolis.

On a vertical hive (or a long Langstroth hive), just replace your inner cover (the cover-board that separates the uppermost hive box from the top) with the propolis collector, the deep grooves facing down.

In a horizontal hive, the propolis collector goes in vertically, like a divider board. First, cut the propolis collector to the width of your hive, wall-to-wall (easily cuts with a sharp utility knife), for a Layens hive, it would normally be 13-5/8” wide. (Do not throw away the cutoff: you can pin it to the wall for additional propolis collection, see below.) Then you have two options.

First option: insert the propolis collector like a divider board after the last frame, with the deep grooves facing the bees. Add another completely empty frame on the other side of the propolis collector, to prop it up.

Second option: for best support, you can attach the propolis collector to a Layens frame using thumb tacks, the deep groves facing out. If your frame has tapered end bars (the top wider than bottom), you can cut back the taper on one side of the frame with a utility knife.

Should the propolis collector go all the way to the bottom?

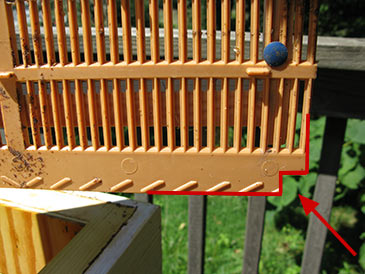

Normally you would want the propolis collector to go all the way to the bottom, so bees can’t get past it and start building comb on the other side. However, if bees find an opening big enough to squeeze through, they may not be able to get back to the nest and will die. So I either leave a small 3/8” gap under the propolis collector (if it is not mounted on a frame, you can create the gap by placing a small twig under it). Or I will cut out two 1/2” square holes in the two bottom corners of the propolis collector to enable any stray bees to get back to the nest.

When to insert the propolis collector

Bees collect the most propolis in late summer/early fall, when the days are still warm (so the resin is still workable) but the nights get cold. With the colder night temperature, bees get the urge to winterize the nest ahead of the freezing weather. So install propolis collectors when nights start getting cool in late summer. Another reason propolis harvest is best during this period is that the hives are still strong, and with nectar flow ebbing, forager bees have more time to devote to collecting resin. So your colony can be producing a very valuable product even when there’s not enough nectar to be making surplus honey!

I normally harvest honey after the first frost (late October–early November), but if propolis collector is to be used, you need to harvest honey and insert the collector about six weeks before the first frost. (Here in the Ozarks in southern Missouri, around September 1.) This gives bees enough time to collect propolis while the weather is still warm. Because resin hardens in low temperature, bees can’t collect propolis in late fall after the first frost. If some of the honey you pull is still not capped and has high moisture content, you can give the frames to another strong colony to ripen and cap.

Once honey frames are pulled and propolis collector is in place, the empty space behind the collector helps stimulate bees’ propolis collection.

Note: don’t put/store any frames (e.g., extracted honey frames) in the empty compartment while the collector is in use. This is because bees can’t pass through it, but small hive beetles can, and they can damage frames stored in the empty compartment.

Positioning the propolis collector for best results

Bees are especially receptive to the cracks / air draft in the part of the hive where they are highly active, at the edge of the brood nest. So if, after pulling honey, you are leaving them 10 frames for the winter (a typical number for a strong colony in Layens hives), but the bees are mostly active up to frame #8, and not so much on frames #9 and #10, then at the time you install the propolis collector, move frames #9 and #10 to the other edge of the nest, between the wall and frame #1. The final arrangement will be: hive wall — frames #9 and #10 (not many bees) — frames #1 through #8 (lots of bees and activity on that last one) — propolis collector (deep grooves facing the bees) — empty space. The idea is to have the comb closest to the propolis collector teeming with bees.

Use strong hives. Beware of small hive beetles

Every propolis collector creates more spaces for small hive beetles (SHB) to hide from the bees, so use them judiciously, selecting vigorous and well-populated colonies for collection. Such colonies will collect much more propolis than weak colonies, and will also be able to keep the small hive beetles in check.

Air draft = more propolis

The movement of air through the collector (draft), and possibly light, strongly stimulate application of propolis. So propping up the hive cover slightly will increase the air flow and propolis collection. If you live in a warm climate with small hive beetles running amok, be very careful about propping up the lid as it will give the beetles the “back-door” access to the hive (not good). If SHB are a problem where you live, ideally cover the top of the empty hive compartment with insect screen (e.g., stapled or tacked into place) and then you can confidently prop the cover up by 1/8” (small enough that robber bees from other hives cannot get in) — this will create stronger air flow but beetles won’t gain access to the brood chamber.

Right genetics

Bee colonies differ tremendously in the amount of propolis collection and application. Many wild-caught colonies are good propolis collectors. But commercial bees have been bred for 100 years to collect as little propolis as possible — so these can collect very little even under favorable conditions. You’ll be able to establish by trial and error which colonies propolize the collector screen well, but it’s a good idea to note in your apiary journal (which I diligently keep) which colonies tend to propolize the corners of the hive, between frames, etc. — use these in preference to “non-propolizers” for propolis collection.

Rotate the collector after 2–3 weeks

Bees start filling the propolis collector screen from the top down. After 2–3 weeks it’s a good idea to check it and if the top half is well filled, rotate it 180° and re-insert, to encourage the bees to finish filling the other half. If the screen is not rotated, a band of slots toward the bottom may be left completely free of propolis. This is consistent with how bees coat the walls of their tree nests — good propolis envelope at the top, but more sporadic application toward the bottom.

Harvesting the propolis collector

A colony that is a good propolizer will fill the collector screen completely before the end of the season. It can be left there for the winter to act as a divider board (unless your climate calls for an insulated divider board), and harvested in the spring. If you do pull it in the fall, replace with a solid divider board. If you see a lot of bees on the last frame (#8 in our example), move frame #10 or both frames #9 and #10 back in their original position at this time, too. But if the bees have redistributed honey reserves, moved into the depth of the nest, and partly abandoned frame #8 by the time you collect the propolis screen, no need to move the frames around. Note that moving frames late in the season creates additional disturbance and breaks propolis seals between the frames, so unless there are few bees on the last frame, I prefer to postpone removing the propolis collector until the time of the spring inspection.

Additional propolis collectors on walls

A good propolis-collecting colony will apply propolis to propolis collectors attached to the walls in the brood nest, too. (Deep side of the collector always faces the bees.) So in addition to the divider-board collectors, you can attach them to any (or all) three walls inside the nest, using thumb tacks. (Of course make sure it does not block the entrance.) These additional wall-mounted propolis collectors are best left in place until the spring inspection, as their removal in the late fall would be too disruptive. (If you must do it in the fall, at least pick a series of days with warm weather in the 60s with the bees active and flying.)

Removing propolis from the collector screen

Fresh propolis is gooey when warm, but becomes brittle in low temperatures. So after removing it from the hive, place your propolis trap in a clean new trash bag and freeze for 24–48 hrs. Remove the bag from the freezer and, with the collector still inside, twist it in all directions, roll it into a tube back and forth, etc. — our propolis collectors have a is very sleek surface and the chunks of propolis will pop out without you having to scrape them off. The trash bag serves two purposes. First, it prevents moisture condensing on the propolis collector and dampening it (not a big deal if it happens because propolis is not easily soluble in water and can be dried out); and, second, the bag keeps all the chunks of propolis contained when you twist the collector-in-the-bag, instead of them flying in all directions.

Small bits of propolis stuck to the collector can be left as-is: they will come out in the next propolis harvest. Or if you leave the collector outside when the bees are flying (esp. in the spring and in the fall), they will salvage and reuse these bits of propolis the same way they clean up the remaining nectar from extracted combs.

Store propolis in a tightly sealed container

Fresh propolis, assuming it is dry, is best stored in a tightly sealed container (mason jar, 5-gallon bucket with a lid, even a plastic ziplock bag) at lowish temperatures (such as unheated garage). Being a resin, propolis is not afraid of freezing and thawing. Storage at room or higher temperature in a container that is not hermetically sealed (e.g., a paper bag or cardboard box) will gradually dry the propolis as the most volatile resins (that constitute the characteristic propolis smell) evaporate, making it harder and less fragrant.

Ants are attracted to propolis. I do not know if this is the aroma, or small residue of honey it may contain. In any case this is another reason to store propolis sealed. Picking out live ants that invaded your propolis storage is not fun.

How to make propolis supple again

If you ever need to make old dry crumbly propolis supple again (e.g., for rubbing inside the swarm traps), heat it at 220°F for 5 minutes — in an oven; inside a small plastic bag placed on the dash board of a car parked in full sun, with windows rolled up; even in a microwave or in boiling water. Apply while it is soft and malleable using a spatula, drywall knife, or a craft stick. (If using a drywall knife and it starts to harden again, put the knife over the flame of a candle to reheat it.) It will harden again as it cools down. (Tip: old / dry propolis can be more easily applied to swarm traps in tincture form — see below.)

Propolis tincture — how to make

If you want to make propolis tincture, best do it right after harvesting (to preserve all the aromatic volatile components). Put the chunks removed from the propolis collector (loose, without compacting) into a mason jar, all the way to the neck of the jar, and cover with pure grain alcohol (such as Everclear, 190 proof, 95% alcohol by volume) — it will fill in the cracks between the chunks of propolis and will start slowly dissolving it. Leave this jar with a tightly fitting lid on in a dark warm place for 6 months, shaking it periodically (ideally twice a week). The propolis tincture will have a rich color of strong black tea; strain it through filtering paper (coffee filter is OK); the less soluble components of propolis will look like gray sediment. It can be left in the jar and go through another cycle after you refill the jar with propolis and Everclear, for an even more complete extraction.

I call this full-strength propolis tincture. If you prefer to make it even more concentrated (so you can call it “double-strength” or “triple-strength” for marketing purposes, of if you want to minimize ingestion of alcohol), just leave the container with filtered tincture open and let part of the alcohol evaporate. Attention: if you forget about it, the alcohol can evaporate completely, leaving you with dry propolis powder. In fact, this is how you can purify propolis full of impurities (and this is why much of propolis is sold in powder form — it has been dissolved in alcohol and then reconstituted, losing much of its fragrance). Just before turning back into powder, the drying propolis tincture becomes a thick, sticky, very fragrant dark-brown ointment — powerful stuff.

Using propolis tincture

Propolis tincture has many uses: add it to toothpaste and cosmetics for its fragrance and confirmed antibiotic properties, use as first-aid antiseptic on small cuts, etc. If taking it internally, bear in mind that propolis may be good for you, but grain alcohol (ethanol) is not. So “drink responsibly” or make triple-strength tincture as discussed above. Water-based propolis extraction could be preferable, but it requires special equipment which is too expensive for do-it-at-home use.

Propolis tincture can be used instead of propolis chunks for scenting new swarm traps — just paint swarm trap walls and bottom with the tincture, using a brush. Alcohol will evaporate, leaving behind a nice thin coating of fragrant propolis for the swarm scout bees to enjoy.

Propolis sensitivity

Some people are sensitive / mildly allergic to propolis. If, for example, you make hand salve or lip balm containing propolis (my favorite kind), it may help many people with cracked skin and chapped lips. But some people will experience greater irritation, reddening, even rash — in which case discontinue use.

Propolis economy

Propolis from chemical-free hives is very valuable and in high demand. You should have no problem selling it at $10/ounce or more locally or online. Value-added products (salves, lip balms, etc.) are even more lucrative, with unlimited potential uses. I’ve seen beekeepers in Eastern Europe sell pieces of fabric impregnated with propolis smell — to put inside your pillow case and inhale propolis fragrance in your sleep (it’s actually very good). Propolis was even rumored to be the secret ingredient in the varnish used by Antonio Stradivari on his best-in-the-world violins. (This rumor is probably not true, but it gives you an idea of propolis’s marketing potential.)

According to researchers, one colony can collect up to 3 lb or propolis / year. This is probably true for ideal conditions, with colonies genetically predisposed to propolis collection, and when colonies are actively managed for propolis collection. Without such special measures, I find 1 lb per colony per year a wholesome harvest for the wild bees in the Ozarks where I live.

PROPOLIS, PROPOLIS TRAPS & OTHER EQUIPMENT AVAILABLE FROM OUR STORE >>

Hives, swarm traps, honey extractors, etc.

Many more guides are in progress, so please join our email list below for more free advice and important updates (no spam; only 2-4 emails per year, and you can unsubscribe at any time). THANK YOU! – we’re working hard to bring you the bees... and the smile!

— Dr. Leo Sharashkin, Editor of “Keeping Bees With a Smile”